NEAT – how to increase your energy expenditure!

- Kamila Gurdek

- Categories: Lifestyle

- Comments (0)

Before we tell you, what’s behind the mysterious acronym – NEAT, its important to understand the concept of energy balance and what makes up our energy expenditure!

What is the energy balance?

Energy balance equation – is the difference between the amount of energy supplied to the body along with food (energy intake) and the amount of energy spent by the body on basic life functions, physical activity and everyday activities (energy expenditure).

We talk about maintaining the energy balance when the amount of energy intake is equal to the amount energy expenditure. A positive energy balance is recorded when we consume more energy than we spent. On the other hand, we have a negative energy balance when the value of energy expenditure is less than energy intake

What makes up the energy expenditure?

There are 3 main components of the energy balance that determine the total energy expenditure (TDEE):

- basal metabolic rate (BMR),

- thermic effect of food (TEF)

- thermic effect of physical activity (TEA)

BMR represents the minimum amount of energy spent for basic body processes and represents about 60% of the total daily energy expenditure of people with sedentary lifestyle. The thermic effect of food (TEF) accounts for about 10-15% of total energy expenditure and is associated with digestion, absorption and storage of nutrients. The third main indicator is TDEE related to thermic effect of physical activity (TEA), which accounts for 15% to 30% of energy expenditure.[2] [3]

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis

TEA can be further divided into thermogenesis of exercise-related activity (EAT) and non-exercise-related activity (NEAT). They differ significantly, because EAT is defined as planned, orderly and repetitive physical activity, which aims to improve health, including training in the gym.

NEAT is a daily activity outside the planned training units. Includes energy expenditure used to maintain and change posture – lying down, standing, walking, climbing stairs, spontaneous muscle contractions, fidgeting, and other daily activities. They are characterized by low intensity. Although unplanned and quite trivial, they can have a very large impact on metabolism, changing our energy requirements over the week. [2] [3] [4]

Meet Emily and Lily!

Emily and Lily are best friends. They have exactly the same height, weight and age, so their BMR is exactly the same. However, their day looks quite different!

Emily works on the other side of the city, doesn’t have a car, chooses morning walks to the office. She likes walking – it relaxes her, which is why she usually returns from work on her feet too. It can take an average of 12,000 steps in one day. She is usually tired after a whole day, but she manages to implement three strength training sessions a week. She would like more, but there is no time. She likes to eat and allows herself to larger portions, and sometimes to go out. Her weight and body composition satisfy her. She also doesn’t feel any problems with her appetite.

Lily works from home. From the morning she sits down in front of the computer, finishes in the late afternoon. After work, she goes to pilates classes. Because they are usually in the evening, outside the city, she commutes there by car. On average, she performs only 1000 steps during the day. She keeps eating and is constantly hungry, especially when she is working from home, right next to the kitchen. She notes that her weight is constantly changing, so she tries to attend pilates classes at least 5 times a week. She sees that Emily can eat more from her and does not understand why this is happening, since she goes to training more often than Emily. She thinks she just has a “slow metabolism.”

As you can see, due to the increased share of NEAT in the case of Emily, the average weekly energy demand is up to 450kcal higher than in Lily! This is the amount of calories corresponding to one nutritious meal!

What if Emily and Lily want to reduce body fat?

In the case of Emily, the energy demand with a 10% caloric deficit, which will allow to start the reduction, is about 2000kcal. Lily will have to consume 1600kcal to be able to record the same weight loss.

Remember! Reduction does not have to be associated with hunger and low calorie supply!

But does it really matter that much?

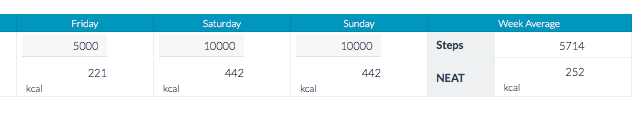

In the example above, Asia performed 12,000 steps a day, resulting in an additional 430kcal for daily energy requirements. However, remember that even a small increase in NEAT can change your energy expenditure! As you can see below, only 5000 steps are up to 221 additional calories!

Calculating the energy needs of our patients, we estimate in our program the average number of steps each day, and further throughout the week. In this way, we can match the exact 24-hour energy demand, individually for a given patient.

And what do the research say?

In one study, people were closed in a small calorimeter chamber (3.3×2.5 m). It turned out that some spent as much as 800kcal per day from spontaneous physical activity alone. This means that all you need to do is just fidgeting to accumulate such a pool of calories! What is interesting, all movements resembling drilling are with very low intensity, and yet significantly increased energy expenditure. [1]

For example, playing or strolling in stores doubles energy expenditure, while deliberate walking involves doubling or triple your energy consumption. [3]

What affects NEAT?

Spontaneous physical activity is the most variable component of 24-hour energy expenditure. In people with a very sedentary lifestyle it is about 15% of energy demand, and in very active people it can reach as much as 50% or more. [3]

It is very difficult to get accurate NEAT estimates because the diversity of these activities is too great. In addition, there are many factors that affect the value of NEAT, including:

- Occupation – the level of activity may vary several times depending on the type of work.

- Industralization – the phenomenon of industralization and the creation of urban environments, is associated significantly with reduced physical activity and a sedentary lifestyle.

- Genetics – there is speculation that genetics directly affect NEAT. Based on studies of twins and families, heredity at the level of physical activity is estimated to be between 29 and 62%.

- Age – physical activity decreases significantly with aging.

- Gender – affects in a more subtle way and depends on the country and place. What’s more, society and cultural customs are important here – including whether women can work both at home and in the public domain.

- Body composition – overweight people seem to have lower levels of activity.

- Education – people with higher education are characterized by greater physical activity in their free time, but in low-income countries, impoverished children show the highest NEAT.

- Seasonality – for example, in Canada, the time spent on activities was 2 times higher in summer than in winter. The difference is visible in agricultural communities, where the amount of work varies depending on the season.

Okay, does this NEAT somehow affect health?

Research indicates that an active lifestyle, with an emphasis on spontaneous physical activity, has many health benefits. A sedentary lifestyle again is associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases.

Metabolic syndrome, obesity, impaired carbohydrate metabolism, including the risk of diabetes may be directly related to low NEAT levels. What should be noted – he may be independent of EAT, i.e. planned physical training!

In the group of people who showed a small amount of fidgeting when sitting for more than 7 hours a day, there was a 30% increase in the risk of death. However, research shows that you only need 15 minutes a day or 90 minutes a week to have a 14% reduced risk of death and a 3-year increase in life expectancy! [2]

A few, quick tips on how to increase your non-exercise activity thermogenesis!

- Consciously pay attention to choose options that require more movement during the day! Instead of the elevator – use the stairs. You have a moment after work – come back on your feet.

- Use your bike! Contrary to appearances, if you live in a city, the bike is your friend. During rush hour it will be the fastest source of transport, while increasing your NEAT!

- Do you want to meet your friends? Instead of a party in the apartment, suggest going for a walk 🙂

- Do you have a lot of phone calls while you work? Instead of sitting at your desk, walk around your office during a conversation!

- When driving a car or public transport, park a little further or get off a few stops earlier and walk this piece on your feet!

- Do you sit in front of computer or have a sedentary job? Fidget! Do not sit still in one position, but constantly change something!

Enter some tips into your life and you will see that after a while it will get into your habit!

| [1] | Levine JA, Schleusner SJ, Jensen MD. Energy expenditure of nonexercise activity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(6):1451-1454. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.6.1451 |

| [2] | Chung N, Park MY, Kim J, et al. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): a component of total daily energy expenditure. J Exerc Nutrition Biochem. 2018;22(2):23-30. doi:10.20463/jenb.2018.0013 |

| [3] | Levine, J.A. (2004), Non‐Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT). Nutrition Reviews, 62: S82-S97. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00094.x |

| [4] | Frühbeck G. Does a NEAT difference in energy expenditure lead to obesity?. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):615-616. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66834-1 |